Professor Christopher Beauchamp explains the history of patent litigation and why America's spirit of invention continues to thrive.

You may have heard that the patent system is in crisis. Every year, the U.S. Patent Office pumps out a record number of patents, many of them vague, overbroad, or drafted to claim inventions that are old or obvious. Worse still, a class of opportunistic entrepreneurs and lawyers have begun to weaponize these patent grants, adopting a business model based on acquiring and enforcing patents and spreading out across the country to threaten everyone from large industrial companies to startups and small family firms. The result is a “patent litigation explosion” that has swamped the federal courts in the hardest-hit jurisdictions and tangled thousands of defendants in vexatious lawsuits. Members of Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court worry that the patent system has become a tool for “speculative schemers” trying to assert patents over “every shadow of a shade of an idea.”

Welcome to the patent predicament of 19th-century America. The rise of “patent trolls” and rampant patent litigation has been a common lament lately, but it’s not a new phenomenon. In fact, the 19th-century patent system not only prefigured many of the present dramas, but was actually far more controversial and litigious than that of the early 21st century.

The numbers alone are startling. Compared with the great wave of patent suits in the middle of the 19th century, the modern- day patent litigation explosion is more of a muffled pop. The rate of lawsuits per patent was more than 10 times higher in 1850 than it is today. At least one federal judicial district in the late 19th century had as many as 1,000 patent cases filed in a single year. For comparison, that amounts to about one-fifth of the number filed in the whole United States in 2014, when the patent system, the economy, and the business of the federal courts were vastly larger.

Next, consider the range of technologies touched by patent contests. Recent hot-button patent fights have involved claims for podcasting, scan-to-email technology, and the various design features embroiled in the “smartphone wars” The last time patent trolls and a litigation explosion created a crisis in the U.S. patent system, America’s spirit of invention not only survived—it thrived. Between Apple, Samsung, and other rivals. In the 19th century, almost every high-profile new technology passed through the courts. Patent battles broke out over water wheels, woodworking, mechanical harvesters, sewing machines, railroad cars, telegraphs, telephones, bicycles, and the electric light—as well as rubber goods, baking powder, barbed wire, fountain pens, cash registers, firearms, photography, and refrigeration. As the eminent historian Daniel Boorstin observed of that period: “The importance of any new technique in transforming American life could roughly be measured by the quantity of lawyerly energies which it called forth.”

For a good example of some misplaced “lawyerly energies,” one might look 19th-century America squarely in the mouth. Rubber dentures became a popular new dental item in the 1850s, following Charles Goodyear’s development of vulcanized rubber. Shortly after the Civil War, a group of lawyers and businessmen acquired the rights to key patents and organized an enforcement entity—a patent troll, in current parlance—called the Goodyear Dental Vulcanite Company. They then embarked on a nationwide campaign to extract license payments from every dentist supplying rubber products. By all accounts, it was a cruelly probing effort. The New York Times reported that “servants of dentists were bribed, nextdoor neighbors were questioned, and intimidation was often resorted to.” Attractive lady spies, “whom no dentist would suspect,” were sent into dental offices to gather evidence of rubber sales. Inflamed by the company’s demands, dentists mounted collective resistance, resulting in more than 2,000 patent suits being filed across the country. The Vulcanite Company’s reign of terror ended only after the architect of its legal strategy, company treasurer Josiah Bacon, was shot to death in San Francisco by a desperate dentist accused of infringement.

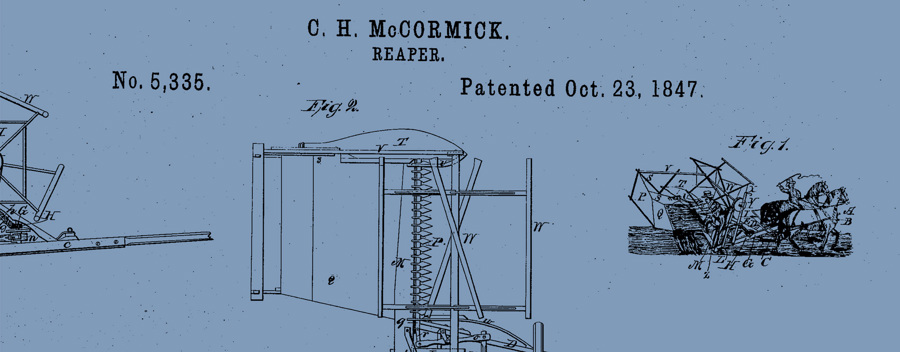

Similar patterns of large-scale patent enforcement recurred elsewhere, albeit in different settings and with different technologies. Early versions appeared in the 1840s, when the owners of valuable patents for water wheels and wood-planing machines started to file hundreds of suits (a huge number for the time) against mill owners and carpenters across New England, the Mid-Atlantic, and the South. Other mid-century patent holders followed suit in seeking to establish patent control, including several who subsequently became famous names in the history of U.S. invention: Samuel Morse of the telegraph; Cyrus McCormick, pioneer of the harvester; Samuel Colt, of the eponymous revolver; and Charles Goodyear himself.

After the Civil War, enforcement campaigns grew even larger. Again, some involved famous inventions. The Bell Telephone Company, for example, filed around 600 suits under Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone patents of 1876 and 1877. In the West, the owners of crucial barbed wire patents brought hundreds of infringement actions against farmers using that vital new farming technology. Other efforts concerned patents no one would remember today. In the booming oil fields of western Pennsylvania, the feared Colonel E. A. L. Roberts flooded the region with lawsuits under his patent for well-blasting charges.

Thousands of suits were filed over a few short years against the “moonlighters” who dared, often under cover of night, to defy his monopoly. And the biggest campaign of all involved an even simpler technology, a widely used technique for obtaining groundwater using a pointed pipe driven into the ground, which was known as the “driven well.” The man behind the driven well patent was Nelson W. Green of Cortland, N.Y., an erratic character who, while commanding a wartime volunteer regiment, had shot one of his captains, been expelled from his church, faced accusations of insanity, and become involved in litigation against his own pastor. Having somehow found the time to invent a driven well in camp, Green obtained a patent in 1868 and began a licensing-and-litigation operation that stretched from Long Island to Oregon. When farmers revolted against demands to pay $10 licenses for a device they considered basic and freely available, Green’s agents filed innumerable lawsuits—hundreds in some counties and several thousand nationwide.

What caused this broader explosion of patent litigation across the 19th-century economy? As you might imagine, systematic data from a century and a half ago is hard to come by; examples like those above have to be painstakingly reconstructed from contemporary newspaper accounts and surviving court documents. Even so, the historical record suggests at least two likely sources of the litigation boom.

One is that the patent system proved, for a while, particularly open to certain kinds of opportunism and rent-seeking behavior. Patents could be extended on a case-by-case basis, either by Congress or the Patent Office, from their standard 14-year term to 21 or even 28 years (and in at least one notorious instance, to more than 40). Well-funded lobbying battles over patent extensions repeatedly erupted in Congress, with “costly and extravagant entertainments” laid on for “ladies and Members of Congress and others” in support of private extension bills. Many of the most-litigated patents were prolonged in this fashion, making them into political as well as legal flashpoints. At the same time, the Patent Office allowed patent owners to “reissue,” or amend, their patents with improved wording, supposedly to correct minor errors but in practice usually to update the patent for use against newer technologies. This practice became so brazen, and so frequently employed to turn obscure old patents into valuable reissued claims, that the Supreme Court eventually decried such grants as “instruments of great injustice and oppression.”

Another engine of litigation was the use of highly aggressive mass-enforcement practices. Attorneys and agents often collected royalties and damages on a commission or contingency-fee basis, which in turn allowed for large and highly motivated assertion campaigns. Suits against large numbers of small-scale technology users—what we would now call “end users,” as opposed to manufacturers or retailers—were common, with farmers a particular target. Especially in the West, patentees took full advantage of the costs facing those sued in a faraway federal court. As one Iowa senator pointed out: “Our people are paying day by day $10, $15, $20… just because it is cheaper to do it than to defend a suit.” To be sure, the reasons for suing small defendants were not purely tactical. One major driver of the number of suits was the scale of business itself. Patentees often had to target individual infringers because their sector contained no large-scale manufacturing firms or retailers to sue, at least before the rise of big business at the end of the 19th century.

The first patent litigation explosion took place in a world very different from our own. Neither the typical business organization nor the typical lawsuit of the 19th century looks much like their modern counterparts. Patent litigation used to be much less expensive, in both absolute and relative terms. Even so, there are some resounding echoes between the two periods.

First, in both eras the patent enforcement system itself became entrepreneurial. Middlemen, lawyers, and business models evolved to become particularly attached to patent litigation and creative in pursuing it. Specialized “patent assertion entities” emerged, including the Goodyear Dental Vulcanite Company and its modern successors, notorious patent trolls such as the Acacia Research Corporation. These are the firms that stretch the limits and norms of patent law. They also tend to account for a disproportionately large number of cases. Just 35 plaintiffs sued a quarter of all patent defendants in the U.S. courts in 2012, for example, mirroring the small number of patentees who dominated the 19th-century scene by filing hundreds or thousands of suits. Some of the most intriguing parallels between the periods of patent activism are cultural, in the form of a “gold rush” mentality enveloping the patent system and altering the self-identity of patent owners and the patent bar.

The second striking similarity lies in the backlash against runaway patent enforcement. Today’s litigation explosion has produced fierce reactions in Congress and the courts, including proposals to improve patent quality, shrink the range of inventions that can be patented, limit end-user suits, reduce damages awards, and require losing parties to pay their opponents’ litigation costs. State governments have prosecuted abusive patent trolls for sending bad-faith demand letters. Firms have joined collective defense associations to resist infringement suits. On many of these points, the parallels with the late 19th century are remarkable. In the 1870s and 1880s especially, farmers and other targets of aggressive patent enforcement formed a political movement to push back against patent abuse and to reform the patent law. The proposed reforms would sound very familiar today: wiping out trivial patents, prohibiting end-user suits, cost-shifting, and reining in damages. Similarly, state governments in the rural Midwest tried to legislate against dubious sellers of patent rights, and big businesses like the railroads organized patent defense associations to smother litigation.

The lessons of the 19th century for today’s patent reform efforts are mixed. On the one hand, the most sweeping legislative attacks on the patent system failed. In the 1880s, farmers’ representatives in Congress had a real chance to transform or weaken patent law, but those efforts were stymied in the Senate. The political furor showed the dangers of a popular backlash—it turns out that going after the little guy is dangerous, if you want to keep patent law above politics—but statutory change ultimately did not do much to improve the situation. The previous patent litigation explosion did ebb, however. By the 1890s and early 1900s, the number of suits was down, and litigation was shifting away from mass enforcement against individuals and toward fewer contests between bigger companies. Some of the decline resulted from courts cracking down on abusive practices by patentees. But much of the reduction in litigation may have followed from economic factors beyond the control of courts or Congress, such as the consolidation of the manufacturing industry into larger and less litigious entities. As big business took hold of the innovation economy, the 20th-century experience of patent law became more stable, with the number of suits rarely creeping above 1,000 per year until the 1990s.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes,” as Mark Twain (himself a patent owner) is reputed to have said. The history of the first patent litigation explosion at least suggests that current events are not unprecedented, which may be reassuring to some. However, it remains an open question whether we should see the 19th-century experience as ominous, because it shows the inevitable rot of opportunism lurking within the patent system, or as reassuring, because it did not break the high-technology economy, which subsequently delivered a golden age of invention and a so-called “second industrial revolution.” In any case, today’s patent lawyers can hold their heads high. No matter how much criticism they may hear about the expense and dysfunction of the patent system, they can rightly respond that they are partaking of a great American tradition.

Christopher Beauchamp is an associate professor at Brooklyn Law School, where he teaches courses on intellectual property and legal history. His first book, Invented by Law: Alexander Graham Bell and the Patent That Changed America, was published by Harvard University Press in 2015. His recent scholarship includes “The First Patent Litigation Explosion,” 125 YALE L. J. 848 (2016), which was selected for inclusion in the prestigious Yale/Stanford/Harvard Junior Faculty Forum last year. He earned his Ph.D. in history from Cambridge University and has received numerous awards, including the Cromwell Dissertation Prize of the American Society for Legal History, the Yorke Prize of the Cambridge University Faculty of Law, and the Levinson Prize of the Society for the History of Technology.

Christopher Beauchamp is an associate professor at Brooklyn Law School, where he teaches courses on intellectual property and legal history. His first book, Invented by Law: Alexander Graham Bell and the Patent That Changed America, was published by Harvard University Press in 2015. His recent scholarship includes “The First Patent Litigation Explosion,” 125 YALE L. J. 848 (2016), which was selected for inclusion in the prestigious Yale/Stanford/Harvard Junior Faculty Forum last year. He earned his Ph.D. in history from Cambridge University and has received numerous awards, including the Cromwell Dissertation Prize of the American Society for Legal History, the Yorke Prize of the Cambridge University Faculty of Law, and the Levinson Prize of the Society for the History of Technology.

This article has been adapted from “The First Patent Litigation Explosion,” published in the Yale Law Journal earlier this year.