Professor Jocelyn Simonson’s Book Talk Explores the Power of Collective Acts of Justice

By Nanette Maxim

Collective acts of justice—through community bail funds, court watching, participatory defense, and people’s budgets—“are ‘radical’ in that they are getting to the root of the question of what justice is and what safety is,” said Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Research and Scholarship Jocelyn Simonson in a discussion of her new book, Radical Acts of Justice: How Ordinary People Are Dismantling Mass Incarceration.

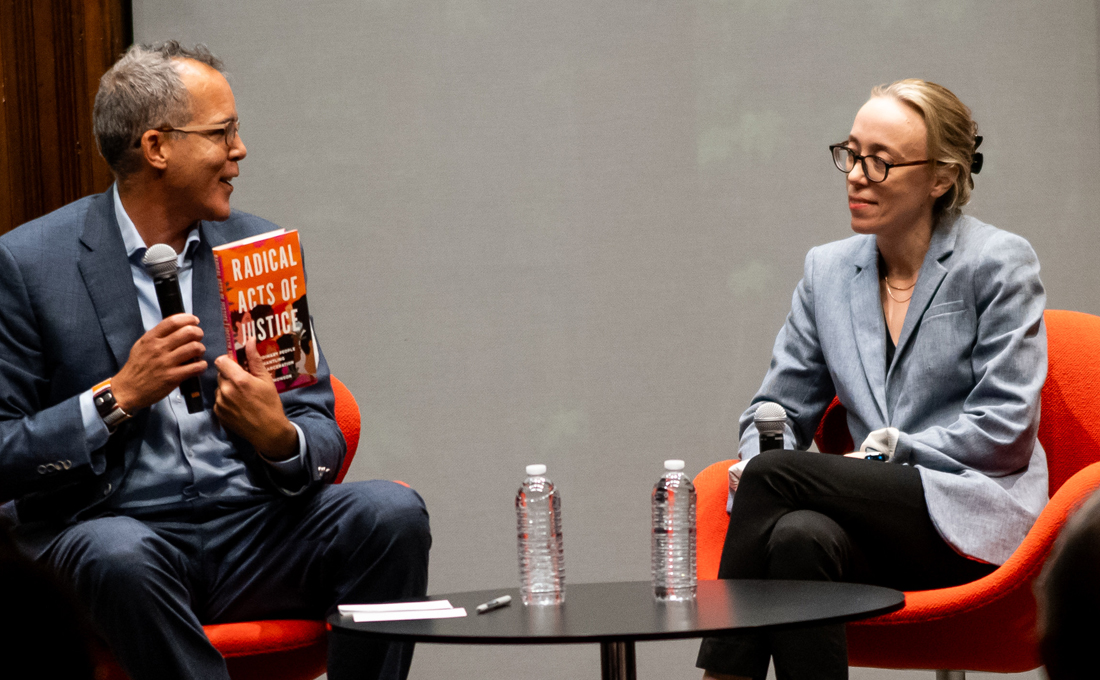

Joining Simonson in conversation presented Oct. 23 at the Center for Brooklyn History, was James Forman, Jr., J. Skelly Wright Professor of Law at Yale Law School, faculty director of Yale’s Center for Law and Racial Justice, and author of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize winner Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. The event was co-sponsored by the Center for Brooklyn History, Brooklyn Law School, and n+1.

Simonson, a former public defender in the Bronx and a longtime criminal law and justice scholar, said the book allowed her to provide a more accessible story illustrating the power behind collective acts of justice, the changes they have enabled, and the challenges they face.

“The acts that I write about in the book are not official acts that come from someone who we’ve declared is allowed to decide what justice is or is seeking justice in a traditional way,” Simonson said. “It’s groups that are going into the world to do what they feel needs to happen…These are regular people, not people we traditionally think of as experts. And the things that come out of these acts are extraordinary.”

Simonson explained the four main tactics or strategies—community bail funds, court watching, participatory defense, and people’s budgets—that are used to collectively help and support those accused of crimes and to redefine “public safety.”

Community bail funds, which have grown from two or three to hundreds nationwide over the last decade, consist of a group raising money and posting money bail or bond, not for people they know but for strangers. They operate out of a larger belief that “putting somebody in a cage when they’re still presumed innocent, just because they can’t afford the amount of bail that a judge has set, is not justice,” Simonson said, adding that nor do the groups believe this makes a community safer.

Court watching groups either sit in a criminal courtroom or virtually observe proceedings—such as arraignments, sentencing, bail hearings —thereby affecting those in the courtroom with their presence.

“Prosecutors, judges, attorneys, and court officers are not used to being observed in this way,” Simonson said, adding that court watchers use social media to share what they have seen, write reports on their observations, and educate others, providing a profound account of “what justice is being done.”

Participatory defense, Simonson said, “involves groups, often led by families, that meet to talk about ongoing cases, to brainstorm what’s happening, to provide support, and to actually work up the case, especially through things like mitigation that might help their case in court.”

This might involve, for example, “putting together a video to explain what somebody’s life is like, to show to a jury,” Simonson said.

People’s budgets, she explained, are collective contestation of the criminal system that “goes beyond the courthouse and into the state house, the city council, and the town meeting.” These groups present alternate budgets to those proposed by lawmakers, that support forms of justice and safety that don’t include punishment, such as restorative justice services, mental health services, violence prevention programs, housing, and education.

“There was a renewed set of uprisings following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor,” Simonson said. “Organizers across the country were joining in larger coalitions in a way that they hadn’t before to think about their local budgets, how much was being spent on policing.”

Forman introduced discussion of the challenges that justice groups face, including from those within the justice system itself. “Why is it,” Forman asked, “that so many people who think of themselves as fighting for justice end up in positions of authority where they don’t do that?”

Simonson explained that some prosecuting attorneys perceive the activist groups as resistance groups coming at the lawyers and judges with little things when the legal professionals are trying to do big things, to serve grand ideas. But the message from the groups, she added, is “No, this is what your district attorneys are doing all day, every day. They’re in this arraignment and bail courtroom and they are asking for bail on the kinds of cases that you said you wouldn’t be bringing, let alone not setting bail on. They are not taking the time to explain what they’re doing. They are not answering the judge’s questions. They are not being responsive. So, you can have grand ideas about changes you want to make, but what are you actually doing?’”

Public defenders, she said, may bristle at the group’s pushback on the expectation of jail time for the defendant. And certain judges simply do not want the public in their courtrooms, Simonson said. Compromise and incremental change, she added, are an inevitable part of the process.

Forman and Simonson also spoke of the dramatic changes in the conversation around these subjects during the past decade, including current law students’ greater preparedness to explore criminal justice in a way that was not imaginable in the 1990s.

“We’re now at a decade of people understanding and learning from each other and national networks talking about how to do this work,” Simonson said. “And as much as the backlash and retrenchment is painful—it leads some community bail funds to close, for example—there is a sense of a grounded understanding of the organizing and power and energy and knowledge that has been built and an underlying confidence in organizing and tactics and the potential for change.”

“What would you say when people ask, ‘How do I get involved, and begin to join to take action?’” Forman asked.

“Part of it is looking around where you are and seeing what can be done,” Simonson said. “The thesis of my book is that when you get together with other people, caring about each other and about what's going on in the world, and you try to help people, you do it collectively, and you do it with a sense of greater purpose. You are going to not just change the individual people but together you'll be changed, and you might even change ideas out there. Collectively, these groups go into this space of so-called justice, and make the impossible possible.”