Scholars Celebrate Book on the ALI’s 100th Year and its History of Collaborative Decision-Making

The American Law Institute (ALI), a professional organization whose mission is to clarify U.S. law and make it more accessible, reliable, and effective for practitioners, academics, and judges, among others, turns 100 this year.

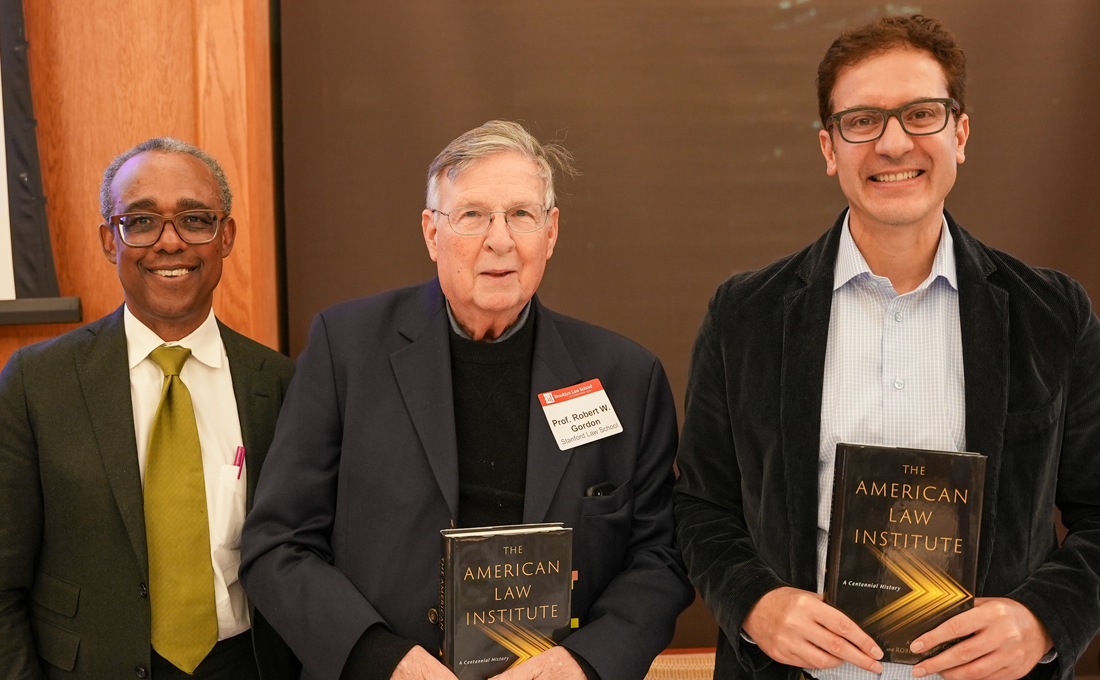

To honor its work, Brooklyn Law School hosted an Oct. 30 discussion of the new book The American Law Institute: A Centennial History featuring: co-editors Professor Andrew S. Gold, associate director of the Center for the Study of Business Law and Regulation; Robert W. Gordon, Professor of Law, Emeritus at Stanford Law School; contributing author Richard R. W. Brooks, Emilie M. Bullowa Professor of Law at New York University School of Law; and moderator, Vice Dean and Centennial Professor of Law Miriam Baer.

The ALI is best known for its “Restatements” of law, in various areas, but it also publishes “model codes” for comprehensive sets of laws, such as the Uniform Commercial Code, which governs all U.S. commercial transactions. In newer, still-innovating fields of law the ALI publishes “principles of law” that are influential not only in courts and legislatures nationwide, but in legal scholarship and education, Gordon said.

The ALI’s history began in the early 1920s, after a committee meeting on improving the nation’s law was chaired by Elihu Root, then the dean of the New York City Bar, and previously U.S. Secretary of War and U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, respectively. Early luminaries of the ALI included Learned Hand, Benjamin Cardozo, and John Henry Wigmore, who were joined by an “august array of law teachers, judges, and practitioners,” Gordon said.

“The committee's report diagnosed what it saw as the root causes of the crisis in the American justice system. It perceived the crisis to stem from the uncertainty and complexity of the law across different jurisdictions, states, and the federal government, all working on hundreds of new cases every year,” Gordon said.

The ALI Restatements were designed to “promote greater uniformity, clarity, and systematic organization of cases in different fields,” he said. Each project was chosen by the ALI’s director and council and assigned a “Reporter” drawn from the legal academy who was in turn advised by a body of experts. Ultimately, said Gordon, the Restatements needed approval by all of the ALI members, in sessions that have been known for their lively and sometimes rowdy discussion.

“To this day, the Reporters read out draft sections of proposed Restatements to the attending members in the ballroom of the Mayflower Hotel in Washington,” Gordon said. “And they vote the sections up or down, and they’re editable by motions on the floor…This is kind of an awesome exercise in deliberative, collaborative decision-making.”

Although the initial membership limit was 500, the ALI now counts 4,700 members, including 2,700 elected members, and has diversified its ranks.

Before partnering with Gold to co-edit the book, Gordon emailed about 100 legal scholars with an interest in private law and history. Most agreed that he needed a co-author for the project, and several recommended Gold, which was the “best advice I’ve ever received,” Gordon said.

Writing about the ALI’s history requires meticulous research into its projects. “Every single draft is preserved in its archives and every single comment on every single draft is preserved. The transcripts of the debates over all the restatements are preserved,” Gordon said. “Writing the history, even on a single Restatement, is a pretty daunting enterprise.”

Gold, who wrote a chapter about the Restatements and the common law with Henry E. Smith, Fessenden Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, said that they examined how Restatements can either “bring about reform or, in some instances, freeze the law,” and how they can best be understood in terms of systems.

“Systems can be artificial, they can also be organic; biological systems are not artificial, and yet they can count as systems,” Gold said. “To the extent that we think of the common law as being a system, it is a relatively organic one in the way that it evolves, whereas the parts that are codified tend to be more artificial, in a sense. And so, we can think of law in areas that are restated as being a kind of hybrid system.”

The systems can have “loose connections between the parts, they don't always entail a certain outcome,” Gold added. “And the Restatements, if you look at them, don't entail a particular outcome either. There is some wiggle room.”

Another key theme that Gold and Gordon explore in the book is that the changes that Restatements bring about can have unexpected impacts. “So, if you think of law as a system, complex systems have different parts, different components that interact with each other, they interrelate, and you make change in one area and have all sorts of ripple effects elsewhere in the system,” Gold said.

The Restatements can stay in place for decades before an update, and may not reform the law. While not as binding as legislation, they have a strong impact, nonetheless. “Courts can ignore them if they choose to do so, but they often do pay attention to them,” Gold said.

Brooks, who wrote a chapter of the Restatements of contracts, described how it involved parties with very different thought processes often clashing with fiery words before ultimately coming to an agreeable document.

Asked by Baer why there were only four discontinued Restatements of law in the 100-year history of the ALI, he credited the institution.

“In the initial projects, just to jump-start it, they had to be successful. Once it was successful, I don’t think projects were taken on lightly,” Brooks said. “And maybe the last thing, is they might have been lucky in the selection of the Reporters. Even more than the projects, the selection of Reporters has been a source of great assurance.”